048: a place in the shade for all

on The Arab Apocalypse, Ziad Rahbani, Walid Al Wawi, the role of the artist

What is an artist on the frontlines of catastrophe? At their best, they are bellwethers of history, translators of tragedy who’ve tasked themselves with bending language—sometimes going as far as shredding it— at a junction where current vocabulary fails to deliver. The function of art, then, is to put language and its vultures on trial, and shepherd collective thought towards truths that in hindsight will have always seemed self-evident.

I think of Etel Adnan’s The Arab Apocalypse, a text more alive today than it was in the 80s.

Where do you want ghosts to reside?

In our wakeful hours there are flowers which produce nightmares

We burned continents of silence the future of nations

the breathing of the fighters got thicker became like oxen’s

Here we are, a world whose heartbeat is held by the ghosts who walk among us. Gaza fills with the living dead, those whose protruding ribs and hollow faces resurrect the nazi german concept of the Muselmann. This century’s living dead is a silenced witness straddling the outer rings of televised death. They offer their testimony to the surviving witness, through an infinite stream of screens and the ever-present option to swipe past. Our comfort creatures and our refusal to give them up are the flowers which produce nightmares.

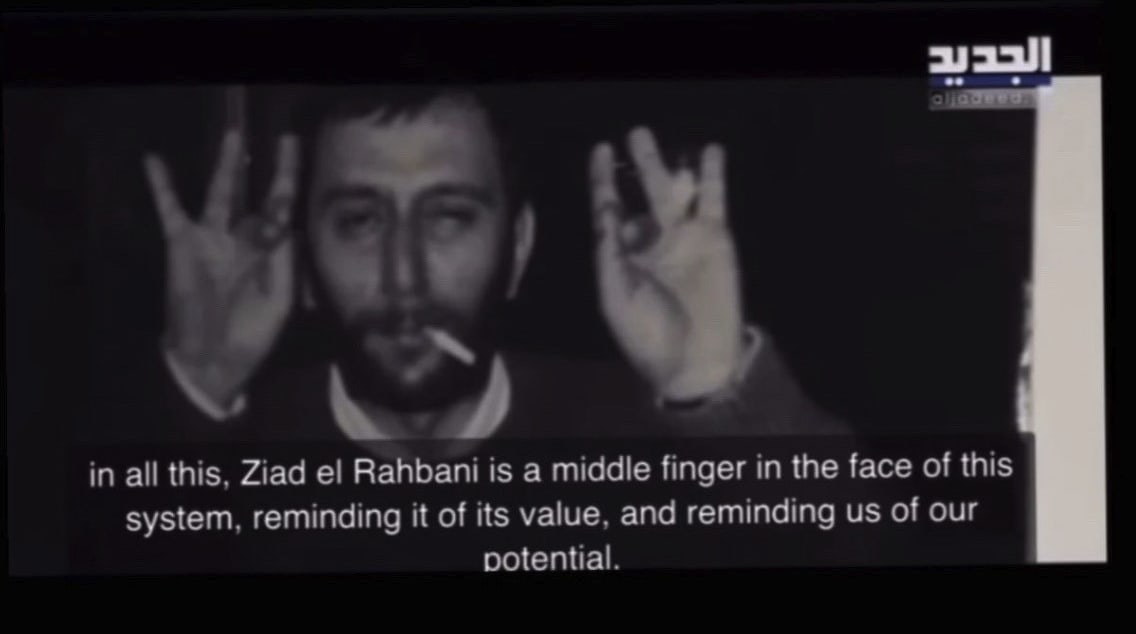

In the wake of his recent passing, I think of Ziad el Rahbani, whom everyone simply refers to as “Ziad,” as though he’s always been everyone’s lifelong friend. A man who was never a stranger to any household and who found his place in every living room, in every college dorm, in every Hamra bar, precisely by owning his choice to be a renegade at a piano. He did so with an unfaltering commitment to liberatory politics and a devil-may-care attitude.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to blue metropolis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.